Family Style: Sonia Gomes

Sonia Gomes’ three-decade-long practice coalesces in textured bronze sculptures in London.

Besides her shock of dyed blue-black hair, the first thing I notice about Sonia Gomes are the fabrics hanging from rails and stacked up neatly behind her in her studio in Pinheiros, São Paulo. These textiles—which range from a hand-embroidered tablecloth that once belonged to a friend’s grandmother to a 50-year-old lace and silk wedding dress—have been gifted to her by strangers over the last two decades. “I rarely go to a store to buy fabric,” says the Brazilian artist, “What I’m interested in has the mark of time, a sense of history.” But she doesn’t get too attached to the materials’ sentimental value: It is their malleable, elastic nature that she likes to work with. Gomes cuts, rips, twists, weaves, stitches, wraps and ties the scraps of cloths into new forms, combining them with quotidian materials like birdcages, driftwood, and wire to create her poetic, organic sculptures that tap into a rich Afro-Brazilian heritage of craft while at the same time, pushing into more abstract territory.

Raised in Caetanópolis, the birthplace of Brazil’s textile industry, Gomes grew up with a grandmother who instilled in her a love of fabrics. As a teenager in the ‘60s she would customize her clothes, although her own artistic inclinations fell by the wayside when she started practising as a lawyer. But her love for craft was never far behind, and at the age of 45 she enrolled in classes at the Guignard University of Art in her home state of Minas Gerais. Having never been exposed to the contemporary art scene before, she found the experience eye-opening and liberating. “I could go to art museums and do what I wanted,” she recalls, “It felt so free and open.” Little by little, her confidence in her ability to be an artist grew, culminating in her first solo show in 2004 at Sandra e Márcio Objetos de Arte gallery in Belo Horizonte. “I felt a great deal of catharsis when that show opened,” she says now. “I cried everything I had to cry and came out of that process more confident and ready to go deeper.”

Yet her real breakthrough did not come until 2015, when she was the only Brazilian artist in the late curator Okwui Enwezor’s Arsenale exhibition at the 56th Venice Biennale. “I thought it was a prank call at first,” she laughs. “I had never been asked to participate in an important institutional show before.” Like fellow pioneers in fiber art like Sheila Hicks and Anni Albers, Gomes has had to fight preconceptions of her work. “Here in Brazil, if you’re Black, what we do is considered craft, not art,” she explains. “But at the same time, I was making what I wanted and I only had myself to please.” Since then, she has gone from strength to strength: In 2018, she became the first living Black woman artist to receive a monographic exhibition at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo. Last year she returned to Italy to show work for the 60th Venice Biennale, and earlier this year she opened her first-ever solo museum show in the United States, “Sonia Gomes: Ó Abre Alas!” at Storm King Art Center.

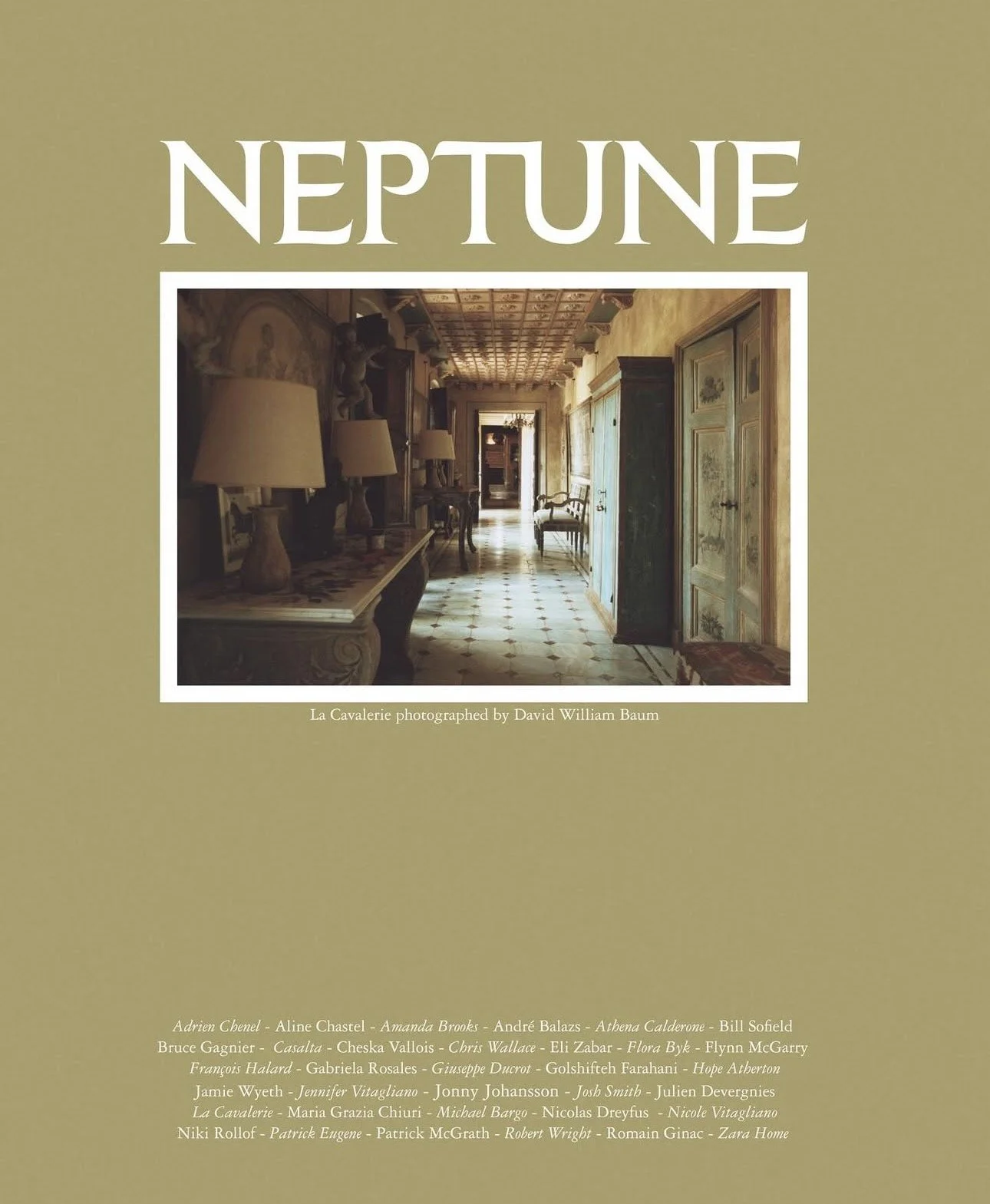

Now she 's opened her first solo London show at Pace Gallery, “É preciso não ter medo de criar.” The title of the show—translated as “one must not be afraid to create”—is drawn from Clarice Lispector’s 1943 novel Near to the Wild Heart and was born of Gomes’ frustration at being pigeonholed as an artist who worked only with textiles. By embracing new materials and experimenting with new techniques, Gomes wanted to express the expansiveness of her universe. Case in point are new bronze sculptures: casts of textile-wrapped tree burls and branches with delicate threads dangling. “It’s a very cold material, very different from what I’m used to,” she observes of her first explorations of the medium.

True to her practice of recontextualising old work into new, a monumental fabric sculpture suspended from the ceiling (Tereza, 2025) fuses a group of Gomes’ previously unrealized pendants from 2021 into one sinuous, biomorphic trailing form. Elsewhere, a piece of cotton fabric—twisted by Bai artisans on China’s Tibetan border in preparation for shibori dyeing and sourced by Gomes from Portobello market in London in 2019—is utilized in three separate pieces: a painting, a wall sculpture, and a pendant. She calls it a coincidence that these fabrics are now being exhibited in the city where she first found them. “I remember being amazed at all the trouble it took to dye and the artisanal way it was handled,” she recalls. “In that way, there were a lot of parallels in my work.”

Even at 77 years old, Gomes keeps up an almost monastic studio practice: every day she spends the mornings at her home before going into her studio at noon where she works until 7 or 8 p.m. at night. “This routine is a pleasure for me,” she says. “I like what I do. I like to work.” After decades toiling in obscurity, she is relishing the newfound opportunities presented to her and her status as a godmother of sorts to a new generation of Brazilian contemporary artists. “I’m very happy to see my work out in the world,” she says, adding, “In my head, I have many projects and new ideas.”